It is not clear from where ISBE

obtained this photograph; it simply

reads Heads of Amorites, akin to

North Africans. From the text on

p. 120, I would suppose this is a

representation from Egyptian

artists.

It is not clear from where ISBE

obtained this photograph; it simply

reads Heads of Amorites, akin to

North Africans. From the text on

p. 120, I would suppose this is a

representation from Egyptian

artists.

Topics: The Philological Perspective

Extra-Biblical Sources—the Amorites Enter into the Fertile Crescent Area

Extra-Biblical Sources—the Amorites Enter into Canaan

Amorites in the Old Testament, a Chronological Approach

Amorites in the Old Testament, a Topical Approach

Charts: Why do we have two general names for the people who occupied the Land of Promise prior to the Jews?

Preface: When I first began this study, I thought of the Amorites as being this small group of nomads who occupied a relatively small plot of land just east of the Dead Sea, who, because of their basic hard-heartedness, lost this territory to the wandering Jews as they moved northward along the Dead Sea for an eastern entrance into the Land of Promise. I originally expected that they could be dispensed with in a paragraph, and perhaps a page if I stretched the doctrine out. However, in the examination of their background, I discovered a people with a rich and powerful heritage, with linguistic connections to the Hebrew of which I was unaware. Like most ancient peoples that we study, we may complete this doctrine with more questions than we had when we started.

It is not clear from where ISBE

obtained this photograph; it simply

reads Heads of Amorites, akin to

North Africans. From the text on

p. 120, I would suppose this is a

representation from Egyptian

artists.

It is not clear from where ISBE

obtained this photograph; it simply

reads Heads of Amorites, akin to

North Africans. From the text on

p. 120, I would suppose this is a

representation from Egyptian

artists. It was a website which actually gave me the short version: The Amorites were members of an ancient

Semitic-speaking people who dominated the history of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine from about

2000 to about 1600 BC. In the oldest cuneiform sources (c. 2400–c. 2000 BC), the Amorites were

equated with the West, though their true place of origin was most likely Arabia, not Syria. They were

troublesome nomads and were believed to be one of the causes of the downfall of the 3rd dynasty of Ur

(c. 2112–c. 2004 BC).

![]() To help with the geographically challenged, Syria is adjacent to and slightly

northeast of Palestine and Arabia is southeast of Palestine. This sort of disagreement is to be expected.

When this people made a splash in the world, we know where

that was. However, where they came from prior to that time, prior

to making their mark in history, is often a matter of speculation.

To help with the geographically challenged, Syria is adjacent to and slightly

northeast of Palestine and Arabia is southeast of Palestine. This sort of disagreement is to be expected.

When this people made a splash in the world, we know where

that was. However, where they came from prior to that time, prior

to making their mark in history, is often a matter of speculation.

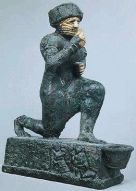

Most of my sources have the Amorites as invading the ancient

eastern world from the north, coming from Syria. Interestingly

enough, even though they are descended from Ham through

Canaan, Egyptian artists represent them with fair-skin, light hair

and blue-eyes.

![]() We have relief pictures of them as well, as you

see on the right.

We have relief pictures of them as well, as you

see on the right.

![]() ISBE therefore suggests that these were

Libyans from North Africa rather than Semitic people (they are

actually descendants of Ham). Amorites in western Asia, on the

other hand, were clearly mixed with other races, their Semitic

language attesting to that.

ISBE therefore suggests that these were

Libyans from North Africa rather than Semitic people (they are

actually descendants of Ham). Amorites in western Asia, on the

other hand, were clearly mixed with other races, their Semitic

language attesting to that.

I. The philological perspective:

1. In the Hebrew, this is Ĕmôrîy (י.רֹמֲא) [pronounced eh-moh-REE], which is transliterated Amorites. Strong’s #567 BDB #57.

2. In the Greek, it is Amorraioi (Αμορραοι) [pronounced a-mor-RAI-oy], which is obviously a transliteration. Strong’s #none.

3. The Akkadian is Amurrû and the Sumerian is Mar-tu. The latter two words are often translated westerner (s). To the Babylonians, they would have been westerners, as they were west of Babylon. ZPEB asks the rhetorical question, why did they call themselves ‘westerners’? and why did other westerners (e.g., the Hebrews) call them westerners? Let me suggest that the name stuck, so that they themselves and other groups of peoples referred to them as westerners.

4. According to ISBE, in the Babylonian period, all settled and civilized peoples west of the Euphrates were

called Amorites, regardless of their actual racial makeup.

![]() At the point of time when the Amorites entered

history, those living around the Euphrates would be considered the center of the world, the cradle of

civilization—and to them, the Amorites are westerners. These people would be east of Palestine (or

northeast of Palestine).

At the point of time when the Amorites entered

history, those living around the Euphrates would be considered the center of the world, the cradle of

civilization—and to them, the Amorites are westerners. These people would be east of Palestine (or

northeast of Palestine).

5. The implication of the meaning of the word is that possibly many of the peoples who in general gravitated toward this part of the world were called Amorites or westerners.

6. In general, certain groups which moved about on the fringes of the Syrian desert in the early second

millennium b.c. called themselves Amurrû.

![]()

7. The settled people in the east used this term as a general designation for the western nomads and those who settled in the west. ZPEB points out that the words Arab and Indian were used the same way (i.e., with a certain amount of imprecision).

8. Given this philological background, the term Amurrû is going to be rather imprecise at times (which would explain its use in 1Sam. 7:14). A Babylonian could conceivably refer to an Israelite as an Amurrû; and certainly the Israelites might refer to almost anyone already living in the Land of Promise (which was, in general, in the area west of the Euphrastes) as Amurrû.

9. Amurrû, during the 2nd millennium b.c., not only referred to a people or ethnic group, but also to a

language and to a geographical and political group in Syria and Palestine.

![]()

II. Extra-Biblical sources—the Amorites enter into the Fertile Crescent area:

1. I should first mention that the Amorites are mentioned but thrice in Durant’s Our Oriental Heritage,

although in one passage, he writes an apology of sorts that such groups of people receive so little space.

His 11th chapter begins: To a distant and yet discerning eye, the Near East, in the days of

Nebuchadnezzar, would have seemed like an ocean in which vast swarms of human beings moved about

in turmoil, forming and dissolving groups, enslaving and being enslaved, eating and being eaten, killing

and getting killed, endlessly. Behind and around the great empires—Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria and

Persia—flowered this medley of half nomad, half settled tribes: Cimmerians, Cilicians, Cappadocians,

Bithyrnians, Ashkanians, Mysians, Mæonians, Carinas, Lycian, Pamphylians, Pisidians, Lyceaonians,

Philistines, Amorites, Canaanites, Edomites, Ammonites, Moabites and a hundred other peoples each

of which felt itself the center of geography and history, and would have marveled at the ignorant prejudice

of an historian who would reduce them to a paragraph.

![]()

2. Ragz-international gives us the best short and dirty on the Amorites: At the beginning of the second

millennium, there was a large-scale migration of great tribal federations from Arabia which resulted in the

occupation of Babylonia proper, the mid-Euphrates region, and Syria-Palestine. They set up a mosaic

of small kingdoms and rapidly assimilated the Sumero-Akkadian culture. It is possible that this group was

connected with the Amorites mentioned in earlier sources; some scholars, however, prefer to call this

second group Eastern Canaanites, or Canaanites.

![]()

3. The fertile crescent is the area which stretches from the Mediterranean Sea along the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers appears to be the location of one of the earliest civilizations. Where these two rivers empty into the Persian Gulf, there were two dominant groups, the Sumerians and the Akkadians, who essentially merged into the Sumer-Akkadians. Because of the rivers, land and trade routes, this was a much coveted area, and peoples moved into it aggressively to take what they could, or gingerly attempting to assimilate and merge with the dominant culture.

4. Sargon the Great appears to be the world’s first dictator, ruling over the Mesopotamian area circa

2500 b.c.).

![]() The Bible Almanac identifies him with Nimrod of Gen. 10:8–10. Gen. 10:8, 10 reads: Now

Cush became the father of Nimrod, and he became a mighty one on the earth. And the beginning of his

kingdom was Babel and Erech and Accad and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. From that land he went forth

into Assyria and built Nineveh and Rehoboth-Ir and Calash and Resen , between Nineveh and

Calash—that is the great city. In the 11th year of his reign,

The Bible Almanac identifies him with Nimrod of Gen. 10:8–10. Gen. 10:8, 10 reads: Now

Cush became the father of Nimrod, and he became a mighty one on the earth. And the beginning of his

kingdom was Babel and Erech and Accad and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. From that land he went forth

into Assyria and built Nineveh and Rehoboth-Ir and Calash and Resen , between Nineveh and

Calash—that is the great city. In the 11th year of his reign,

![]() Sargon the Great, sent an envoy to the land

of the Amurrû, intending to procure materials for his great building projects. The record of this event

reads: the land of the West to its limit his hand reached, he made its word one, he set up his images in

the West, their booty be brought over sea. Apparently there are omen texts which back this up. One

reads: he went to the land of the Amurrû, defeated it, and his hand reached over the four regions [of the

world]. Another reads: he went to the land of Amurrû...struck it for the second time [and] his

warriors...brought him forth from the midst. This could refer to two expeditions, which would allow for one

to take place in the 3rd year and another in the 11th year. According to ancient records, Sargon’s envoy

must have gone as far as Mari on the Euphrates and on into Syria.

Sargon the Great, sent an envoy to the land

of the Amurrû, intending to procure materials for his great building projects. The record of this event

reads: the land of the West to its limit his hand reached, he made its word one, he set up his images in

the West, their booty be brought over sea. Apparently there are omen texts which back this up. One

reads: he went to the land of the Amurrû, defeated it, and his hand reached over the four regions [of the

world]. Another reads: he went to the land of Amurrû...struck it for the second time [and] his

warriors...brought him forth from the midst. This could refer to two expeditions, which would allow for one

to take place in the 3rd year and another in the 11th year. According to ancient records, Sargon’s envoy

must have gone as far as Mari on the Euphrates and on into Syria.

5. The Amorites successfully infiltrated the fertile crescent around 2500 b.c. and eventually set up small kingdoms (more like towns) throughout. There was a king of the Amorites in this area who seemed to have dominion over several of these cities who was himself subject to Babylonia during the dynasty of Ur.

6. There are Sumerian and Akkadian inscriptions which refer to the Amorites as a desert people who were

unacquainted with civilized life, grain, houses, cities, government.

![]()

7. Gudea, the king of Lagash (circa 2125 b.c.), tells of his expedition to the far

northwest to obtain materials for the building the temple for Ningirsu, which was

his city-god. He took a great many raw materials from various sources in the

west, all from the land of the Amurrû. His account does not imply

A stone statue called

worshiper of Larsa.

A stone statue called

worshiper of Larsa.

that there was any sort of organized nation known as Amurrû—just an vast region populated with westerners.

8. Whereas most of my sources indicate that this movement of the Amorites into the Mesopotamian area was peaceful and much earlier, The Bible Almanac portrays them as invaders from Canaan and the Arabian Desert and says that they wrestled control from the then Elamite rulers in 2000 b.c. The ruler who emerged from all this was the famous Hammurabi, whom all my sources identify as being Amorite.

9. Although the Amorites had been infiltrating the fertile crescent for centuries,

around 2000 b.c., they moved into Babylonia in much greater numbers, taking

over several towns, including Larsa and they are partly responsible for the

collapse of the 3rd dynasty of Ur.

![]() They were the dominant people in western

Asia roughly during the time of Abraham’s wanderings. In fact, both Syria and

Palestine were known to the Babylonians as the land of the Amorites.

They were the dominant people in western

Asia roughly during the time of Abraham’s wanderings. In fact, both Syria and

Palestine were known to the Babylonians as the land of the Amorites.

![]() There was apparently a great

influx of Semitic peoples into the Babylonian area.

There was apparently a great

influx of Semitic peoples into the Babylonian area.

![]() Amar-Suen, a Sumerian ruler in Ur (circa 2040 b.c.),

constructed a fortress along the lower portion of the Euphrates River; the name of the fortress was that

which Keeps Away Tidnum (Tidnum was equivalent to Amurrû). This apparently did not do the trick, as

the Amorites penetrated deeply into Sumer (circa 2025 b.c.), cutting off Nippur and Isin in the north from

the southern capital of Ur. Two Amorites, Ishbi-Erra and Nablanum, both took control of the towns Isin

and Larsa, indicating a weakening of the power of the rulers of Ur. In about 1895 b.c., Sumuabum, an

Amorite sheik, reigned as king in Babylon. The significance is twofold: an Amorite is ruling over Babylon

and his fifth successor is the famous Hammurabi (circa 1792 b.c.).

Amar-Suen, a Sumerian ruler in Ur (circa 2040 b.c.),

constructed a fortress along the lower portion of the Euphrates River; the name of the fortress was that

which Keeps Away Tidnum (Tidnum was equivalent to Amurrû). This apparently did not do the trick, as

the Amorites penetrated deeply into Sumer (circa 2025 b.c.), cutting off Nippur and Isin in the north from

the southern capital of Ur. Two Amorites, Ishbi-Erra and Nablanum, both took control of the towns Isin

and Larsa, indicating a weakening of the power of the rulers of Ur. In about 1895 b.c., Sumuabum, an

Amorite sheik, reigned as king in Babylon. The significance is twofold: an Amorite is ruling over Babylon

and his fifth successor is the famous Hammurabi (circa 1792 b.c.).

10. Within a few centuries of their influx into the fertile crescent, an Amorite dynasty was established. These kings traced their ancestors back to Samu or Sumu, who ISBE suggests is possibly Shem of the Old Testament (which would not be keeping with the Scriptural ascendancy). Babylon was their capital city, which tells us that they had dominion over the Sumer-Akkadians. This time period is known as the Old Babylonian period. One of the kings of this time period was Khammu-rabi, whom ISBE identifies with Amraphel of Gen. 14:1.

11. Yamkhad-Aleppo, which is the Kingdom of Syria, could be considered an Amurrû kingdom.

12. The Kingdom of Mari in Mesopotamia could also be considered an Amurrû kingdom.

13. Even the great Hammurabi of Babylon (circa 1792–1750 b.c.) could be called an Amorite.

![]() Douglas

also agrees that there was an Amorite dynasty established in Babylon, whose most famous king was

Hammurabi.

Douglas

also agrees that there was an Amorite dynasty established in Babylon, whose most famous king was

Hammurabi.

![]()

14. Shamshi-Adad I, an Amorite, ruled Assyria from about 1814–1782 b.c. He controlled the territory from east of the Tigris into Syria. His son, Yasmakh-Adad, ruled in Mari for 17 years (1796–1780 b.c.).

15. At this point in time, the power and influence of the Amorites was greatest. They were ruling Assyria in the northeast, Babylonia in the southeast and Yamkhad-Aleppo in the west.

16. Some of the Amorites were still roaming the land around Mari. According to Douglas, Hammurabi, in circa 1750 b.c., had conquered Assur and Mari, making them Amorite states as well. Often, the way these things are determined by historians is based upon linguistic evidence. That is, the language of the surviving texts are examined, and many conclusions are based upon that.

17. There came about an organized Kingdom of Amurrû around 1400 b.c. (this would have been about the time that Israel was entering into the Land of Promise). Although ZPEB covers the names of the rulers and some of their treaties, they are not completely clear as to where this kingdom was (although, I assume that this was in the vicinity of Mari and the mountains of Lebanon). This kingdom continued into beginning of the 13th century b.c.

18. I must admit that it seems strange to me that these people receive barely a mention in Durant’s Out Oriental Heritage, yet they ruled over important territory during important times and had their own established kingdom involving relationships with Egypt and the Hittites.

19. I should point out that the various sources which I have examined seem to be contradictory and confusing at times—even within their own isolated accounts. From what I can gather, it seems as though the Amorites came from the north and entered into the Babylonia area circa 2500 b.c. and then went into Palestine around 2200 b.c. (although it is not clear that they went from the Mesopotamian region into Palestine). They appear to have been the dominant force in the Mesopotamian region around 2000 b.c.

20. In any case, Hammurabi’s dynasty only lasted three generations. Apparently the Assyrians took control which was put to a halt by the Kasshites in 1750 b.c. Apparently the Kasshites and the Assyrians warred for the next 5½ centuries, during which time Israel was in bondage to Egypt, Israel left Egypt, Israel took over the land of Canaan, and Israel began the period of time known as the judges.

III. Extra-Biblical Sources—the Amorites Enter into Canaan:

1. The Amorites appeared to have entered into the Palestine area circa 2200 b.c. The evidence is that their

burials which were distinguished by a distinct type of pottery and weapons. These things have been

discovered in Tel Ajjul, Jericho and Megiddo.

![]() ISBE puts them as the dominant force in Palestine and

Syria (which is north of Palestine) during this time; the Babylonians referred to this area as the land of

the Amorites (which was later known as land of the Hittites).

ISBE puts them as the dominant force in Palestine and

Syria (which is north of Palestine) during this time; the Babylonians referred to this area as the land of

the Amorites (which was later known as land of the Hittites).

![]()

2. Obviously, we have some disagreement here. When did the Amorites enter into the fertile crescent? 2500 b.c. or 2000 b.c.? Was their entry peaceful or was it an invasion? Did they come from Canaan or did they come from the north? Did they enter Canaan after conquering the Mesopotamian area or did two separate groups of Amorites enter both into Mesopotamia and into the land of Canaan?

3. According to ZPEB, the first actual organized kingdom of Amurrû’s occurs during the Amarna Age (circa 1500 b.c.), which doesn’t exactly make sense if we have an already established Amorite kingdom in the fertile crescent area. Perhaps, they meant the first organized kingdom in the land of Canaan.

4. One of the ways in which we track a people is the discovery of artifacts with their language upon them.

Between 1600 and 1100 b.c., the language of the Amurrû disappears from Babylonia and the mid-Euphrates region. Instead, it crops up in the Syria and Palestine regions. In 100 b.c., Assyrian

inscriptions used the term Amurrû to refer to a portion of Syria, all of Phœnicia and all of Palestine;

however, it was more of a geographical term than one which referred to a people, kingdom or language.

![]()

5. To confuse matters somewhat, we have later mention of the land of Amurrû, but it appears to refer to the general area of Syria-Palestine (which is slightly south of the Kingdom of Amurrû), which appears to be the area that the Amorites lived in prior to the Amarna Age as well.

6. Again, as I mentioned, I have sources which give me contradictory information. ISBE says that the

Amorite kingdom continued to exist down to the time of the invasion of the Land of Promise by the

Israelites. They indicate that the Amorites only went as far south as Naphtali, but that their kingdom

extended to the borders of Babylonia.

![]() This does not agree with Scripture, which has some Amorites

in the central and southern portions of the Land of Promise. On the other hand, such changes can take

place in as little as 50–100 years. During this time period, Egypt had exerted enough influence over the

Amorites that their kings became mere vassals of Egypt. When the Egyptian kingdom began to break

up under Amenhotep IV, the Amorites turned to the Hittites in the north for protection. At that point,

according to ISBE, the Hittites ruled over the land of Palestine all the way to the Egyptian border. ISBE

puts the time frame for this around 1400 b.c. The problem with this time frame is that they then have the

Amorites losing their foothold in western Israel and establishing their kingdom in eastern Israel circa

1200 b.c. Israel took this same land from the Amorites in 1400 b.c. or so. So, if we push the dates from

ISBE back 200–250 years, then it all meshes relatively well.

This does not agree with Scripture, which has some Amorites

in the central and southern portions of the Land of Promise. On the other hand, such changes can take

place in as little as 50–100 years. During this time period, Egypt had exerted enough influence over the

Amorites that their kings became mere vassals of Egypt. When the Egyptian kingdom began to break

up under Amenhotep IV, the Amorites turned to the Hittites in the north for protection. At that point,

according to ISBE, the Hittites ruled over the land of Palestine all the way to the Egyptian border. ISBE

puts the time frame for this around 1400 b.c. The problem with this time frame is that they then have the

Amorites losing their foothold in western Israel and establishing their kingdom in eastern Israel circa

1200 b.c. Israel took this same land from the Amorites in 1400 b.c. or so. So, if we push the dates from

ISBE back 200–250 years, then it all meshes relatively well.

7. Once Israel dispossesses the Amorites in the east, the Amorite kingdom disappears. There are still scattered Amorite cities throughout western Palestine—enough, in fact, to earn the inhabitants of the west the general term Amorites.

IV. The Amorite language is of great interest, as ZPEB speculates that Canaanite, Moabite, Ugaritic and Phœnician and even Aramaic languages are actually branches of the Amorite family of languages. The importance of this language is that there are some words which are found exclusively in the Mari texts and the Old Testament.

V. Amorites in the Old Testament, a chronological approach:

1. The Bible gives us the actual origins of the Amorites in Gen. 10:16. Canaan is the father of Sidon, Heth, as well as the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites (Gen. 10:15–18; see also 1Chron. 1:16). We might reasonably suppose, by the forms of their names, that Sidon and Heth were actually sons of Canaan, and that the others were either sons of mistresses, grandsons or great-grandsons.

2. Even though the people of Palestine were a mixed bag of various races, the Bible authors often refer to

the inhabitants of the land as being Canaanites (and the bulk of them are).

![]() Similarly, because the

Amorites did not move as a cohesive whole, but seemed to move as distinct groups, occasionally

Scripture refers to the people in the Land of Promise as being Amorites. We find this usage in

Gen. 15:16 Joshua 24:15, 18 and possibly in Joshua 24:12.

Similarly, because the

Amorites did not move as a cohesive whole, but seemed to move as distinct groups, occasionally

Scripture refers to the people in the Land of Promise as being Amorites. We find this usage in

Gen. 15:16 Joshua 24:15, 18 and possibly in Joshua 24:12.

![]()

3. Most of the time, the Amorites are portrayed as the individual groups that they are. In Gen. 14, we have

several groups of various races battling against one another for possession of a portion of Palestine. The

Amorites are a settled group in the land (there are apparently settled and independent Amorites

throughout the mid-eastern world) and political leader, Chedorlaomer, along with several allies, in putting

down a rebellion against him, conquered the Amorites in Hazazon-tamar.

![]() Gen. 14:1–7. Abram had

apparently evangelized some individual Amorites during this same time period and they were allied with

him (Gen. 14:12–13). They helped Abram retrieve his nephew Lot, who had been caught up in all this

and was taken prisoner (Gen. 14:14–24).

Gen. 14:1–7. Abram had

apparently evangelized some individual Amorites during this same time period and they were allied with

him (Gen. 14:12–13). They helped Abram retrieve his nephew Lot, who had been caught up in all this

and was taken prisoner (Gen. 14:14–24).

4. The history of the Amorites in Palestine obviously did not end in Gen. 14. That reference was to one group of Amorites. Apparently, they pervaded the land, yet some were redeemable. During the time of Abram, his allies were Amorites. The implication is that they were converts of his. However, when God told Abram of what was to happen in the future of his descendants, He speaks of the iniquity of the Amorite not yet being complete (Gen. 15:16). This was a reference (1) to the various populations in the land, and not simply to those who were Amorites and (2) this indicated that a large portion of the population in the land was Amorites.

5. Now let’s deal with that passage. God is speaking to Abram, telling him of what was to be. “As for you,

you will go to your fathers in peace; you will be buried at a good old age. Then, to the fourth generation,

they will return here, for the iniquity of the Amorite is not yet complete.” (Gen. 15:15–16). At that time,

Abram had at least three Amorites that he was allied with, indicating that they were not negative toward

Abram, and therefore, not negative toward his God. We have a man whose racial origin is unknown,

![]() but who acts as a priest for Abram in the previous chapter, indicating that

Jehovah God has a place in the Land of Promise even prior to the influx

of the Jews from Egypt.

but who acts as a priest for Abram in the previous chapter, indicating that

Jehovah God has a place in the Land of Promise even prior to the influx

of the Jews from Egypt.

6. In the same context, we have various racial and political groups

enumerated, and the Amorites are given as one of many groups

whose land will be given over to the Israelites. On that day,

Jehovah made a covenant with Abram, saying, “To your

descendants, I have given this land, from the river of Egypt as

far as the great river, the river Euphrates—the Kenite, the

Kenizzite, the Kadmonite, the Hittite, the Perizzite, the

Rephaim, the Amorite, the Canaanite, the Girgashite and the

Jebusite.” (Gen. 15:18–21).

![]() God makes a similar promise to

Moses: “I have come down to deliver them from the power of

the Egyptians, and to bring them up from that land to a good a

dn spacious land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the

place of the Canaanite and the Hittite and the Amorite and the

Perizzite and the Hivite and the Jebusite.” (Ex. 3:8). This is

repeated in v. 17. A similar list is given in Ex. 13:5 23:23 33:2

34:11 Deut. 7:1 20:17 Joshua 3:10 9:1 24:11 Judges 3:5

1Kings 9:20–21

God makes a similar promise to

Moses: “I have come down to deliver them from the power of

the Egyptians, and to bring them up from that land to a good a

dn spacious land, to a land flowing with milk and honey, to the

place of the Canaanite and the Hittite and the Amorite and the

Perizzite and the Hivite and the Jebusite.” (Ex. 3:8). This is

repeated in v. 17. A similar list is given in Ex. 13:5 23:23 33:2

34:11 Deut. 7:1 20:17 Joshua 3:10 9:1 24:11 Judges 3:5

1Kings 9:20–21

7. Sometimes, when these lists are given, the author is much more specific in terms of where the various groups of people lived. Joshua 11:3 13:2–6

8. One of the most interesting, if not initially confusing, statements

made concerning the Amorites is given in Gen. 48:21–22: Then

Israel said to Joseph, “Listen, I am about to die, but God will be with you and He will bring you back to the land of

your fathers. And I give to you one portion more than your brothers, which I took from the hand of the Amorite with

my sword and my bow.” One suggested interpretation is that this is Gen. 34 when Jacob’s sons avenged their

sister Dinah. This is Israel’s

(Jacob’s) only recorded run-in with the Amorites,

![]() and it is more by way of his sons,

Simeon and Levi, who take revenge on them on behalf of their sister, Dinah, who was raped by a Hivite

and it is more by way of his sons,

Simeon and Levi, who take revenge on them on behalf of their sister, Dinah, who was raped by a Hivite

![]() who then

had the nerve to ask their family for Dinah’s hand in marriage. The sons of Jacob clearly took some of the wealth

of that group of Hivites, but there is no indication that they took any land. Another suggestion is that this refers back

to an unrecorded incident in where Jacob took land from some Amorites. Both interpretations are faulty because,

when Jacob moved to Egypt, he essentially forsook his holdings in the Land of Promise and really had nothing to

give Joseph by way of real estate holdings—he had none! In other words, what Jacob is saying to Joseph had not

yet occurred. We tend to think in past, present and future tense, and the Hebrew does not have that sort of a tense

system. So, when we translate a verse like this, it sounds as though Jacob is presently giving this land to

Joseph—land which he, Jacob, had taken from the Amorite in the past. However, this is not the case. Jacob is

presently giving Joseph a double portion of land, which Israel, as a people, will take in the future with their relatively

primitive weapons. Understanding this passage in this way makes perfect sense, as each of Joseph’s sons,

Ephraim and Manasseh, will receive a portion of land, thus fulfilling this prophecy. In fact, Manasseh will receive

a portion of land on both sides of the Jordan River, one which was specifically taken from the Amorites, meaning

that, (1) Joseph is given a double portion, one to each son (generally something which is reserved for the firstborn)

and then (2) Jacob gives Joseph one additional portion of land, that which is specifically taken from the Amorites,

which would be East Manasseh.

who then

had the nerve to ask their family for Dinah’s hand in marriage. The sons of Jacob clearly took some of the wealth

of that group of Hivites, but there is no indication that they took any land. Another suggestion is that this refers back

to an unrecorded incident in where Jacob took land from some Amorites. Both interpretations are faulty because,

when Jacob moved to Egypt, he essentially forsook his holdings in the Land of Promise and really had nothing to

give Joseph by way of real estate holdings—he had none! In other words, what Jacob is saying to Joseph had not

yet occurred. We tend to think in past, present and future tense, and the Hebrew does not have that sort of a tense

system. So, when we translate a verse like this, it sounds as though Jacob is presently giving this land to

Joseph—land which he, Jacob, had taken from the Amorite in the past. However, this is not the case. Jacob is

presently giving Joseph a double portion of land, which Israel, as a people, will take in the future with their relatively

primitive weapons. Understanding this passage in this way makes perfect sense, as each of Joseph’s sons,

Ephraim and Manasseh, will receive a portion of land, thus fulfilling this prophecy. In fact, Manasseh will receive

a portion of land on both sides of the Jordan River, one which was specifically taken from the Amorites, meaning

that, (1) Joseph is given a double portion, one to each son (generally something which is reserved for the firstborn)

and then (2) Jacob gives Joseph one additional portion of land, that which is specifically taken from the Amorites,

which would be East Manasseh.

![]()

9. In Num. 13:29, the spies return with a report as to which group lives where in the Land of Promise: “Amalek is living in the land of the Negev and the Hittites and the Jebusites and the Amorites are living in the hill country, and the Canaanites are living by the sea and by the side of the Jordan.” (Num. 13:29). Deut. 1:7, 19–20 places them in the same area. At that point, the Israelites began to whine and moan, accusing God of dropping them into the hands of the Amorites (Num. 14:1–4 Deut. 1:27).

10. Israel, although they were warned not to make any military moves into the new land (this was after their

night of moaning and crying), an army pushed its way into the hill country and they were chased out by

the Amorites

![]() (Deut. 1:19–20, 27, 44).

(Deut. 1:19–20, 27, 44).

11. By Num. 21, the Israelites have stopped their wandering (actually, I believe that they stayed in the same place in the desert wilderness for the bulk of that time), and were now moving north along side the eastern side of the Dead Sea, with the intentions of entering into the Land of Promise from the east. From there they journeyed and camped on the other side of the Arnon, which is in the wilderness that comes out of the border of the Amorites; for the Arnon is the border of Moab, between Moab and the Amorites (Num. 21:13). Recall that the Amorites lives in various groups throughout the ancient mid-eastern world. Therefore, there is nothing amiss when they are said to occupy the hill country in a previous point, although they occupy a much greater piece of land here. At this point, Israel sends messengers to the Amorites, asking for safe passage through their territory. Israel is looking to take the Land of Promise and not the land in which they were traveling. They promised to travel along the King’s Highway (so that they could be easily observed) and that they would not drink water from the wells of the Amorites (Num. 21:21–22). Sihon, the ruler of the Amorites, not only refused, but gathered his people to go out against Israel in the wilderness to go to war with them. Sihon had previously taken this land from the Moabites and was hell bent on retaining his ownership of said land (Num. 21:26). However, Israel defeated the Amorites in battle, taking all of the Amorite cities (Num. 21:25, 31–32). The defeat of the Amorites on the east side is mentioned several times afterward (Joshua 9:10 12:1–5 13:7–23 24:8 1Kings 4:19 Psalm 135:11 136:17–21).

12. The tribes of Reuben, half of Manasseh and Gad all chose to live east of the Jordan. Moses gave them this territory; Reuben took the lower half of the Amorite territory and Gad took the northern portion (Gad’s territory extended up to the Yarmuk River). Num. 32:33, 39

13. The taking of the eastern territory of the Amorites and the dividing up of the land of Amorites between Gad, Reuben and Manasseh is mentioned several times in Scripture; often this victory is mentioned by way of encouragement, so that the Israelites realize that God is with them in battle. Deut. 2:24–3:17 31:4. Other groups of Peoples in the Land of Promise were cognizant of this great victory as well (Joshua 2:10).

14. After this great set of victories east of the Jordan, Moses spoke to Israel, which is the bulk of the book of Deuteronomy. Deut. 1:3–4 4:44–49

15. There were Amorite tribes west of the Jordan. Both names—the Amorites and the Canaanites—are used

to represent all the people west of the Jordan. Now it was, when all the kings of the Amorites who were

beyond the Jordan to the west and all the kings of the Canaanites, who were by the sea, heard how

Jehovah had dried up the waters of the Jordan before the sons of Israel until they had crossed, that their

hearts melted and there was no spirit in them any more, because of the sons of Israel (Joshua 5:1). We

find a similar passage in Joshua 7:7–9, where Joshua bemoans Israel’s position to the Lord after being

defeated at Ai: “Alas, O Lord Jehovah, why did You ever bring this people over the Jordan, to deliver us

into the hand of the Amorites, to destroy us? If only we had been willing to dwell beyond the Jordan! Oh

Lord, what can I say, since Israel has turned their backs before their enemies? For the Canaanites and

all the inhabitants of the land will hear of it, and they will surround us and cut off our name from the earth.

And what will You do for Your great name?” In this second passage, it is clear that there are other groups

in the land besides Amorites and Canaanites (and all the inhabitants of the land).

![]()

16. That there were at least five groups of Amorites still living in the hill country is confirmed in Joshua 10,

when there is an alliance of Amorites formed against Gibeon (which had sided with the Israelites).

Specifically, read Joshua 10:3–6, 12. Gibeon, and the cities adjacent to it, who made a treaty with Joshua

in Joshua 9 were probably a mixture of Hivites

![]() (Joshua 9:7) and Amorites

(Joshua 9:7) and Amorites

![]() (2Sam. 21:2).

(2Sam. 21:2).

17. The Amorites lived between the tribes of Dan and Joseph (Ephraim and Manasseh). They exerted enough pressure on Dan so that the tribe of Dan was unable to come down into the valley. The tribes of Joseph, on the other hand, made the Amorites into forced labor. Judges 1:34–36

18. God warns Israel about the gods of the Amorites in Judges 6:10, which means Amorite is being used in the general sense.

19. Even long after the Amorites east of the Jordan had been defeated, this area was still known as the Land of the Amorite (Judges 10:8 1Kings 4:19).

20. That God had promised to deliver and then delivered Israel out of the hands of several hostile groups, including the Amorites, is mentioned in Judges 10:11.

21. Jephthah tries to settle things amicably with the Ammonites in the east by reminding them of Israel’s original trek northward on the east side of the Salt Sea. This involved a veiled warning of what happened to the Amorites when they opposed Israel. Judges 11:17–27

22. Although the Amorites are prominent in the Books of the Law and Joshua and Judges, we find only an occasional mention of them after that. Sometimes, they are only alluded to.

1) Under Samuel, Israel took back the land which the Philistines had taken from them and there was a time of peace for Israel in the land (although it is unclear as to how long that lasted). The passage reads: So there was peace between Israel and the Amorites (1Sam. 7:14b).

2) The Gibeonites are identified as being a remnant of the Amorites when Saul slaughters them in 2Sam. 21:2.

3) The land east of the Jordan is still referred back to as the country of Sihon, king of the Amorites, in 1Kings 4:19.

4) Solomon apparently subdued, but did not destroy, the various non-Israelites groups still living within Israel. 1Kings 9:20–21 2Chron. 8:6–7

5) Twice, the idolatry of kings of Israel and Judah are associated with the idolatry of the Amorites. 1Kings 21:26 2Kings 21:11

6) After the dispersion of Judah, there is concern expressed relating to the intermarriages between Israelites and various other racial groupings, including the Amorites. Ezra 9:1

7) Some Levites commemorate God’s giving of the Land of Promise to Israel and giving them victory over the various peoples in the land, including the Amorites (Neh. 9:8).

23. There are only two mentions of the Amorites in the prophets, and this is because most of the prophets

wrote when the Amorite was history (Solomon’s making the Amorites into Israel’s slave force pretty much

was near their end in recorded history, as far as I am aware).

![]()

1) Ezekiel mentions Amorite once, calling the mother of Israel a Hittite and the father of Israel an Amorite. This remark had two implications: (1) the land of Palestine was so filled with heathen groups of peoples that there was too much by way of intermarriage between the Israelites and the heathen. The result was less of a connection to the True God of the Universe. (2) Even when there was no intermarriage, the Israelites sometimes fell into idolatry, making this a metaphorical remark about Israel’s spiritual condition. Ezek. 16:3, 45

2) Amos looked back on Israel’s taking of the Land of Promise from the Amorite, which term is used in the general sense. Amos 2:9–10

VI. There are several ways the term Amorite is used in the Old Testament, and it may be more worthwhile, as a conclusion, to approach this topically rather than chronologically. Joshua, in his final message of Joshua 24 (actually, it was a fitting final message, although Joshua 23 was probably his deathbed address), used the term Amorite in most of these different ways:

1. There is a specific, actual racial grouping known as Amorites, who moved throughout the eastern world, exerting a tremendous amount of influence. They appeared to blend into various societies without destroying those societies. Gen. 10:15–6 Joshua 12:8 24:11 1Kings 9:20–21

2. Amorite is used of one group which was east of the Jordan. Israel conquered them when moving toward the Land of Promise up along the east side of the Salt Sea. Num. 21:26 Joshua 12:2 24:8 Judges 11:17–27 1Kings 4:19 Psalm 135:11 136:17–21

3. Amorite, like the term Canaanite, is used in a general sense for the people found in the Land of Promise whom Israel displaced. Gen. 15:16 Joshua 24:12, 15, 18 1Sam. 7:14 Amos 2:9–10

4. There are at least two instances where we might reasonably assume that Amorite stands in for the Amorites, Girgashites, Hivites, et. al. Ezra 9:1

5. When used in the general sense, Amorite is often associated with the heathen gods of Palestine. Joshua associates these in Joshua 24:15 and we find it again in Judges 6:10 1Kings 21:26 2Kings 21:11 Ezra 9:1 Ezek. 16:3, 45

6. There are several important passages where it is unclear whether Amorite is being used in the general or the specific sense. 2Sam. 21:2

VII. I must admit to ending this study with many more questions than I began with. I had a great many things cleared up by my sources and have a better perspective of the Amorites; however, on the other hand, I still have developed a lot more questions, which is to be expected of any ancient civilization, and particularly, a race which intermingled so much with other races.

VIII. The most important thing that we should get from all this is, the Amorites were not some uncivilized, small tribe of heathen who walked on and off the stage of history over the period of a couple hundred years. They may have begun as uncivilized nomads, but they eventually made a cultural impact, a portion of which (the laws of Hammurabi) can be said to have had an influence on law for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The cities and areas that they ruled over included significant portions of the mid-eastern world stretching across the fertile crescent all the way into Palestine.

Bibliography |

1. The Bible Almanac, J.I. Packer, Merrill C. Tenney, William White, Jr.; ©1980 Thomas Nelson Publishers; pp. 20, 99. 2. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon; Hendrickson Publishers; Ⓟ1996; pp. 57. 3. The Englishman’s Hebrew Concordance of the Old Testament, George Wigram; Hendrickson Publishers, Ⓟ1997; First Printing, Appendix p. (5). 4. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia; James Orr, Editor; ©1956 Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Ⓟ by Hendrickson Publishers; Vol. I; pp. 119–120. 5. Werner Keller, The Bible as History (second revised edition); New York, 1981; pp. 85–86. 6. New American Standard Bible, Study Edition; A. J. Holman Company, ©1975 by The Lockman Foundation. 7. The New Bible Dictionary; editor J. D. Douglas; ©Inter-Varsity Fellowship, 1962; Ⓟby W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; pp. 31, 61. 8. The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible; Merrill Tenney, ed., Zondervan Publishing House, ©1976; Vol. 1, pp. 140–143. |

It is clear, when examining the sources of many the articles above that they have examined more ancient and better sources. However, there are so many hours in a day, so that, in order for me to do what I need to do, I need to stand upon the shoulders of hundreds of great Christian men who have preceded me. |

Websites |

1. http://ancienthistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa030900a.htm (the article is by N.S. Gill and © 2000-2002 N.S. Gill). 2. http://ragz-international.com/amorites.htm 3. |