Written and compiled by Gary Kukis

These studies are designed for believers in Jesus Christ only. If you have exercised faith in Christ, then you are in the right place. If you have not, then you need to heed the words of our Lord, Who said, “For God so loved the world that He gave His only-begotten [or, uniquely-born] Son, so that every [one] believing [or, trusting] in Him shall not perish, but shall be have eternal life! For God did not send His Son into the world so that He should judge the world, but so that the world shall be saved through Him. The one believing [or, trusting] in Him is not judged, but the one not believing has already been judged, because he has not believed in the Name of the only-begotten [or, uniquely-born] Son of God.” (John 3:16–18). “I am the Way and the Truth and the Life! No one comes to the Father except through [or, by means of] Me!” (John 14:6).

Every study of the Word of God ought to be preceded by a naming of your sins to God. This restores you to fellowship with God (1John 1:8–10). If we acknowledge our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness (1John 1:9). If there are people around, you would name these sins silently. If there is no one around, then it does not matter if you name them silently or whether you speak aloud.

Taken from lessons #004–005 in the Luke series.

|

||

|

|

|

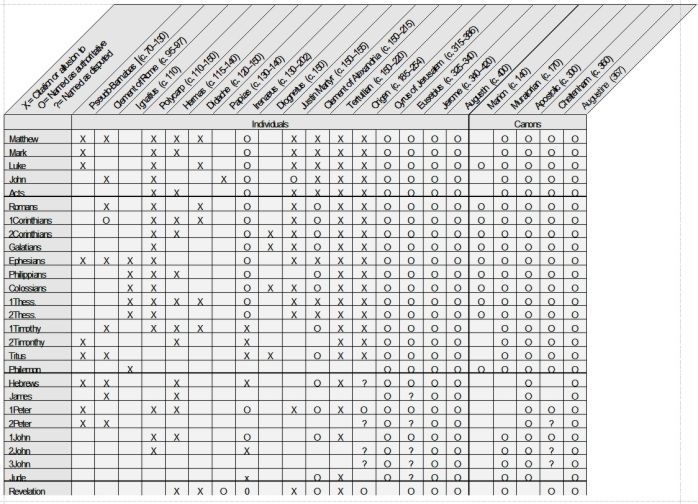

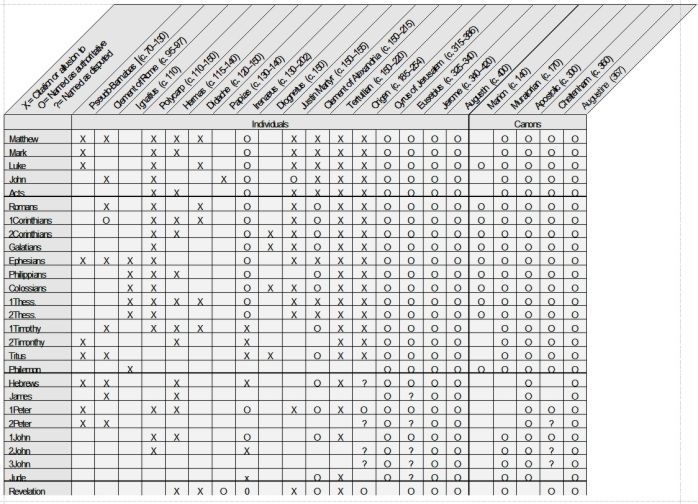

Geisler and Nix NT Canonicity Chart (a graphic) |

Geisler and Nix Translation and Council Chart (a graphic) |

|

Preface: Believers are often curious about the actual background of the ancient manuscripts that we have—how many are there, and where are they? There is also the question, who decided what books are in the Bible and when did this happen?

Before we move any further along in this study, allow me to personally encourage you to focus upon the process and the study of each verse and each lesson, rather than being overly concerned about completing the book of Luke. It is a great feeling to go all the way through a book in the Bible and to understand most of it. But, that can be a long journey, depending upon the book itself. Luke is quite a long biography of the Lord.

When I was younger, my family took a trip from California to Ohio by train. That trip, which took around 3 days, was an adventure in itself. We saw beautiful landscapes, met interesting people, and had a fascinating ride. This trip was every bit as important as arriving in Ohio and doing what families do once we got there.

The same will be true of this study of Lukian biography of Jesus. Enjoy the journey; do not focus on the completion of this study, as I have not even the slightest idea how many lessons will be involved. My intention is to thoroughly study this particular book, yet being mindful not to get bogged down. Also, there will be a few instances where we examine at specific biographical incidents in more detail than what Luke does (I can only think of 2 or 3 incidents where I would like to do this). There are also sections of Luke which lend themselves to extremely important doctrines for the believer.

The LXX (the Septuagint) and the preservation of Scripture:

There is a very important event which takes place during this Intertestamental period: the translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. The world, at that time, was speaking more and more Greek (because of the conquests of Alexander the Great). The Jews were finding themselves spread throughout Alexander’s kingdom; and increasingly, more of them spoke Greek and fewer of them spoke Hebrew. At some point, it became clear that the Jewish people needed their Scriptures written in the Greek language rather than in Hebrew, which was becoming somewhat of a dead language.

Translating the authoritative books required that they actually determine the inspired (or authoritative) texts of the Old Testament. No one was going to translate just any Hebrew writing and throw it into the canon of Scripture; but we actually do not know what steps were taken to determine the proper texts, what texts were used, or if anyone really understood what it meant for the text to be inspired. Was this list of books already known and agreed upon?

Deuteronomy is a very significant book regarding the topic of inspiration as almost everything in this book was written by the man Moses and not quoted from God. Yet, this book has, from the very beginning, taken to be authoritative—every bit as authoritative as portions of Exodus which read, Thus saith the Lord. It is quite remarkable for Deuteronomy to be seen like that, but it seemed to be a natural acceptance. Interestingly enough, the acceptance of Deuteronomy as authoritative, to the best of my knowledge, was never really discussed theologically—not in the Hebrew writings, anyway. I am not aware of any rabbis who found the acceptance of Deuteronomy as being authoritative to be a remarkable thing. By the time they got around to writing commentaries and opinions, the authoritative nature of Deuteronomy was a given.

During this time period between the testaments, the canon of Scripture for the Old Testament was settled. We do not have any idea how exactly this happened. People just accepted certain books as being authoritative. I am unaware of anyone writing any deep dissertation at that point in time about what it meant for writings to be inspired by God nor do we have lists of the authoritative books developed by this or that group. Just, somehow, certain books were accepted as being authoritative; and these are the books which were read in the synagogues. It is these books that would be translated into other languages, as the Jews were dispersed throughout the world at this time. The Greek translation of the Old Testament, called the Septuagint or the LXX, was common and in use during the time of our Lord (it was often quoted from directly by the disciples), and most guess the translation to be made around 200 b.c.

People speaking Greek; people speaking English: Because of Alexander the Great, the great conqueror, koine Greek became the universal language; and most everyone spoke that language (just as many people today speak English).

People throughout the world speak English today for two reasons: the famed British Empire and the United States. The British Empire was established by Great Britain, where they went all over the world and conquered various lands, bringing to these lands the gospel of Jesus Christ, law and order, and the English language. As Great Britain became less devoted to the Word of God, its kingdom began to diminish. However, the United States stepped into Britain’s place. Although we do not have conquered lands all over the world as the Brits did, we have economic, military and cultural influence—but more important than those, we have a spiritual influence on the rest of the world. This is because the gospel of Jesus Christ, taken abroad by thousands of missionaries from the United States, who have been in virtually every country of the world. Because of WWII, we also have air bases and military bases all over the world.

Generally speaking, it is United States policy to protect our citizens all over the world, whether they be tourists or missionaries.

People who are 20 years or more younger than me do not appreciate the influence of the United States throughout the world. In my teens, it was almost an accepted fact that, at some point, WWIII would happen—probably between the free nations and the communist nations. However, that cold war only heated up on a limited number of fronts, and it was nearly always confined to relatively small geographical areas.

As long as the United States continues to send out missionaries, we can rest assured that our economic and political power will remain strong and influential all over the world. But, if we turn toward human solutions and away from the gospel, our power and influence throughout the world will disappear, just as it did for Great Britain. Either some other nation will step up (like South Korea) and take our place in the world, or the world will become a battleground of a hundred warring nations again.

When it comes to the canonicity of the New Testament, we understand the issues which were brought up and what made a book a part of the canon; but we do not have a similar set of criterion for the Old (that we are aware of). The scribes continued to preserve the Hebrew manuscripts and this Greek translation provided another witness to which books were understood to be canonical.

The Hebrew manuscripts and the manuscripts of this new Greek translation were both preserved, but by different groups of people. The Jewish scribes continued to preserve the Hebrew Old Testament; and the Christians preserved the Greek translation of the Old Testament. There were also other ancient translations which were made, and all of them act as sort of a cross-check. Both Testaments were translated into Latin, Syriac (also know as Aramæan) and Arabic. Each translation was preserved by a different groups of men in a variety of nations subject to a variety of cultures.

By preserved, I mean that copies of the manuscripts were made on regular intervals, with various checks in place to insure the accuracy of the text. In most cases, when new manuscripts had been completed, the old ones were thrown away—often burned or completely destroyed. But, bear in mind, there is all this possible cross-checking which took place, attempting to insure that the copies are accurate. Old manuscripts could not be easily handled or read after a time, so they were not just discarded, but destroyed.

Today, I can place a Latin manuscript next to an Aramaic manuscript next to a Hebrew manuscript (and we have internet access to most of these), and easily compare them for differences in order to determine the most accurate text. What is remarkable is, the text is very consistent. If I was required to use Saint Jerome’s Latin manuscripts as my starting text, I would be teaching the exact same thing as if I chose the Greek texts instead. There is no Roman Jesus, Arabic Jesus or Greek Jesus. It is not that case that each tradition is infested with the customs and culture of that particular language and people.

As an aside, so that there is not confusion, let me point out that, the text of the original Hebrew manuscripts is the text which is God-breathed. On the one hand, we have copies of copies of copies of those original manuscripts; but these ancient manuscripts in other languages, preserved by other peoples, serve as a check on our current Hebrew manuscripts. My point is, is I could use the Latin OT as my fundamental text, and the teaching which came from that would be virtually identical to teaching from the original Hebrew text.

What we would expect is, one group would begin to modify the text, to suit their cherished beliefs and traditions, but that did not happen. There are differences in all of these manuscripts, but they are not, for the most part, substantive differences. There are in existence many English Bibles which are translated from different origins: some come from the original Hebrew and Greek transcripts; some were translated from the Aramaic; and some were translated from the Latin manuscripts (if you use e-sword, you can have English texts which were translated from any one of those specific languages).

The Ancient Manuscripts themselves:

Now, if you were given some random English translation of the Old Testament, without you knowing its origin, you would be unable to say, “I know that this came from the Greek translation, because of all the Greek references and Greek ideas which have clearly crept into the text.” You simply would not be able to distinguish one from the other, unless you were particularly scholarly in this specific area. The reason is, there are no Greek images, references or ideas in the Greek translation; just as there are no specific Roman ideas, images or references to be found in the Latin manuscripts. They are not perfectly in synch with one another; but their differences are insignificant. There are some very serious problems with the Catholic church today; but none of these can be blamed on Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin (the common language of his day) around a.d. 400. He did an excellent translation from the Hebrew into the Latin.

My point here is, we know that the text of the original Hebrew has been preserved, because at least 4 or 5 groups preserved parallel texts in different languages. For instance, first the scribes and later the Masoretes preserved the Hebrew texts. The early church preserved the Greek manuscripts. The Catholic church—which became quite corrupt as it consolidated religious and political power—still preserved accurate Latin texts. Now, we can take these texts and examine them side-by-side, and see that there is very little difference between them. No matter which group we are speaking of, they clearly had a reverence for the text before them and therefore did not attempt to corrupt it with their contemporary cultural influences.

There are some very specific linguistic differences and let me explain one particular difference, by way of illustration. In the Hebrew, when speaking of a man’s face, a plural verb is used, because Hebrew people understood the face to be a collection of physical features. We in the English use the singular noun face. So, there are times when a noun is plural in one language yet singular in another—the correct number simply suits the language being used. So, when I am reading an English translation and come across the phrase the face of Moses, and then I check the Hebrew and find that it literally reads, the faces of Moses, I don’t suddenly conclude that Moses originally had two or more heads. I understand that the English and the Hebrew are different in that respect.

Similarly, definite articles are used in different ways. So, whereas the God is commonly found in the Greek; we rarely say the God in the English. God is just God. He is not more fully God in English by throwing the definite article the in front of it. So, most of the differences between the ancient manuscripts preserved in those ancient languages are matters of how the language was used. There is no meaningful difference between the God in the Greek; and God as we use it in the English. Interestingly enough, it is just the opposite with the word for Lord. In the English, we always use the definite article before the word Lord (unless He is being directly addressed); but the Greek almost never uses the definite article before Lord. There are probably more of these sorts of linguistic differences between ancient manuscripts than any other category of difference. One language uses words in one way; another language uses those same words, but slightly differently. So, these kinds of differences are found when comparing Hebrew to Latin to Greek manuscripts/translations.

You may be surprised, but the oldest complete and nearly complete Hebrew manuscripts that we have of the Old Testament goes back to a.d. 1008, the Leningrad Codex (there are earlier Hebrew manuscripts, but they are not complete—for instance, the Cairo Codex—a.d. 895—has the prophets). Ancient, hand-copied Old Testament manuscripts of any significant size are quite rare, and that is because old manuscripts would be copied and then destroyed. This is because when a set of manuscripts became old and difficult to read, they would be copied; and the old manuscript would be purposely destroyed. But these witnesses by other groups of preservationists preserving these same manuscripts, but in a different language, act as a check on what we have.

When it comes to ancient manuscripts, there is a very significant witness. We have partial set of manuscripts known as the Dead Sea Scrolls which was a very ancient library. These scrolls date back to 100 b.c. (or earlier) and include Greek translations of the Old Testament (no manuscript is complete, due to the flimsy nature of the 2000 year old manuscripts). These were discovered around 1947 and various manuscripts continued to be unearthed for the next several years. As a result, we have manuscripts 1100 years older than our oldest manuscripts. Yet, the differences are trivial. As time passes, things are spelled differently. As time passes, grammar changes (even in a rarely used language). So these changes would be reflected when comparing the Dead Sea Scrolls to the manuscripts which are from the 12th century; but substantive differences are rare. Furthermore, substantive differences which actually may change or modify a doctrine are virtually non-existent.

I have translated about the first third of the Old Testament word-by-word and I have come across one serious substantive error. If memory serves, Saul asks for the Ark to be brought to him; but it should have been the ephod that he asked for (he wanted to know some information that he could trust). These two words in the Hebrew are not much different. So, some scribe erred and accidentally wrote ark when he should have written ephod. That is the biggest, most significant problem that I observed in the first third of the entire Old Testament. This is one of the very few times when context and logic force me to say, “The word here should be ephod, not ark.” For the average person, this does not stand out as a substantive difference; but if you know what these things are, then it is. However, this substantive difference does not cause me to panic and think, “I need to go back and rework the doctrine of the Ephod; this changes everything!” Even with that error, there are no changes to be made in discussions of the Ark or the Ephod.

One of the reasons that we can be so certain of the text and what it means is, a huge amount of the Bible is narrative. I have never sat down to consider the percentages, but, as a guess, perhaps half the Bible is narrative (or something which approach narrative). In a narrative, you can often rephrase this or that sentence, and still end up with the same story. Minor mistakes by scribes over the years do not invalidate the text or give us a whole new set of doctrines. It is hard the screw up a narrative.

Preservation of the New Testament Manuscripts:

The preservation of New Testament manuscripts is quite another story. There are manuscript scraps which date back to the 2nd and 3rd century a.d. And, whereas discussion of OT manuscripts can be limited to fewer than 10 significant manuscripts, there are perhaps 26,000 Greek manuscripts of the NT. In the New Testament, there are perhaps a half dozen places where the text is questionable (the end of Mark I recall as being the most significant textual problem). However, for the most part, there are very few words in the NT which are in doubt.

The point I am making is, despite there being some errors in the text, these errors do not affect the overall doctrines that we extract from the Bible. These errors do not disturb a careful systematic theology which is the result of a careful examination of the Scriptures.

There is a great deal written about the inspiration of the Biblical text today; and there are perhaps a half dozen or more theories as to what it means for the Biblical text to be inspired. Geisler and Nix present 8 different theories of what it means for Scripture to be inspired in their A General Introduction to the Bible (a must-have book for any serious Christian, despite the vanilla-sounding title).

Today, we have developed a doctrine which explains how the Bible is to be understood and interpreted; and we know all about the false theories of inspiration which have been used by others. For instance, there is one very subjective approach where the Bible becomes the Word of God. That is, someone reads it, and suddenly, he recognizes that portions of what he is reading go deep into his soul; and he knows that the Bible has become the Word of God for him.

There is another theory where the Bible contains the Word of God. That is, the Bible was written and preserved by imperfect men, so we know that there is a lot of dross in the Bible; but, if you look carefully, you can find the stuff which is really the word of God (many people use this approach suggest that the miracles are just nonsense added in by the superstitious). Both of those theories are false approaches to understanding the Bible.

The correct way to understand the word of God can be explained by the verbal, plenary approach. That is, every single word, phrase and sentence is the word of God and, simultaneously, the words of man. These words are inspired by God, but not in such a way that the writer of Scripture is a secretary taking dictation. That author’s feelings, thinking, experiences, vocabulary and grammar all contribute to both the content and the writing style of each book. So, this is why the books of John and Luke are so different in style and subject matter, even though each is a biography of Jesus. Nevertheless, each book is still inspired by God; each book is still fully the Word of God, and, as such, perfectly accurate—doctrinally and historically.

I mentioned that we do not know how the Old Testament books were chosen or decided upon; but there seems to be almost no disagreement here (the exception is the intertestamental books known as the apocrypha—which books are accepted by the Catholic church as divinely inspired and by no one else—insofar as I know).

The New Testament books have, on the other hand, simple and specific criteria by which they were determined to be in the canon: (1) they had to be written in the 1st century. Those making a determination of canonicity (and there were many people who did this) would not accept some book which is know to have been written in the 2nd or 3rd century. They know that is phony. (2) Each acceptable book must be written by a known apostle or a man closely associated with an Apostle (like Mark or Luke). There is one major exception to this and that is the book of Hebrews, the author of which no one knows (but many people have a theory). It is a book that is so obviously doctrinal and important to the early church that it had to be accepted, even though no one knows who wrote it.

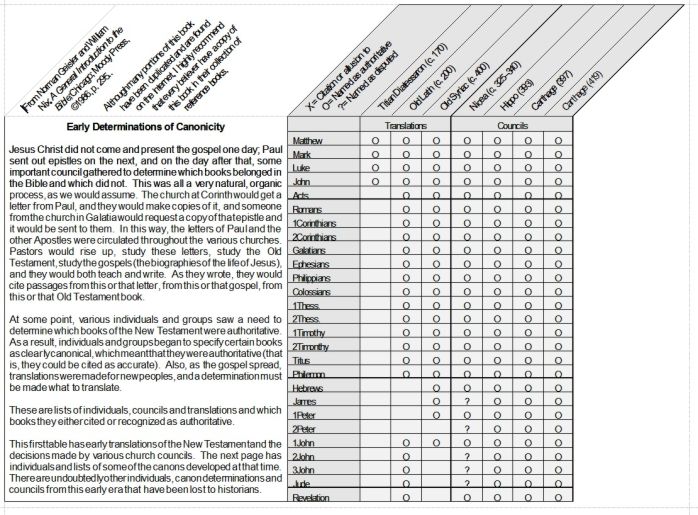

Geisler and Nix NT Canonicity Chart (a graphic); from Introduction to the Bible, ©1968, p. 193. I redid the chart, splitting it into two parts, because it was hard to read.

This is a fantastic chart which tells us that, right from the 1st century, people were trying to determine which books of that era were authoritative. Which books (which all circulated separately throughout the ancient world) could be trusted as accurate portrayals of the Lord or could be read in order to understand correct doctrine? There are 17 individuals who we know about, dating from a.d. 70–400 who made reference to various books and letters in their own writings. Given that this is who we know about today, no doubt there were 10x or even 100x as many writers who referenced specific books in the first 4 centuries of the new era.

You will note that, as time went on, more and more people did not simply refer back to these books and letters, but they began to treat them as authoritative (that is what the O’s mean).

At the same time, some individuals and some groups began to define what the New Testament canon was (now, bear in mind that this all takes place before anyone fully appreciated what canonicity in the realm of theology really means). You can see that Muratorian (circa 170), Barociccio (circa 206—not listed above) and Apostolic (circa 300) listed almost the same canon that we have today. Jerome, Augustine, and Athanasius (350–400) had the exact same canon as we have today (I see that I made an error in my chart and listed Augustine twice).

But besides these individuals, there were translations and councils which also put together lists of the canon.

Geisler and Nix Translation and Council Chart (a graphic): from Introduction to the Bible, ©1968, p. 193. This is the second half of the chart. As you see, Geiser and Nix divided these into 4 sets of witnesses: individual writers, specific canons, translation, and councils.

Early translations into other languages needed to figure out which books needed to be translated into another language. Also, various councils would meet with representatives and scholars attending from various churches, and they would come together to discuss and set forth what they believed the canon of the NT to be. As you see, there are at least 3 ancient councils who came up with the exact same list of books that we use today.

There are so many people today who think our canon of Scripture was developed by the Catholic church who just put out a list and that was final. As you can see, these books were discussed for 4 centuries. Furthermore, we do not have a translation into Aramaic with one set of books, and a translation into Latin with a slightly different set of books. It took time, it took a great deal of discussion and, no doubt, debate; but a canon was decided upon.

What is very important to note is, none of those listed above appear to have advocated for the Gospel of Saint Thomas or the Apocalypse of Peter or any of the other weird, non-canonical books (there were dozens). There is nowhere a list of books who got really close to being included in the NT canon, but just missed out. There is another list of books from that general era known as the Pseudopigrapha; also known as, the books rejected by everyone. Eusebius called these books “totally absurd and impious.”

You will notice by the charts that there was very little difficulty in determining which books did not belong in the canon, no way, no how. The problems were with books that we accept as a part of the canon: Revelation, because it was weird; Hebrews because it could not be attributed to an author; and some of the epistles because they were too short. The Pauline epistles were pretty much universally accepted; the general epistles required more discussion.

In the end, we have the canon that we have, and there are no serious theologians throughout the years who argue that some spurious book was left out but it should not have been; or that we need to take another look at Philemon.

The best way to understand this is, the canon was established by God. He allowed us to recognize it.

|

|

|

|

|

|