These studies are designed for believers in Jesus Christ only. If you have exercised faith in Christ, then you are in the right place. If you have not, then you need to heed the words of our Lord, Who said, “For God so loved the world that He gave His only-begotten [or, uniquely-born] Son, so that every [one] believing [or, trusting] in Him shall not perish, but shall be have eternal life! For God did not send His Son into the world so that He should judge the world, but so that the world shall be saved through Him. The one believing [or, trusting] in Him is not judged, but the one not believing has already been judged, because he has not believed in the Name of the only-begotten [or, uniquely-born] Son of God.” (John 3:16–18). “I am the Way and the Truth and the Life! No one comes to the Father except through [or, by means of] Me!” (John 14:6).

Every study of the Word of God ought to be preceded by a naming of your sins to God. This restores you to fellowship with God (1John 1:8–10). If we acknowledge our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness (1John 1:9). If there are people around, you would name these sins silently. If there is no one around, then it does not matter if you name them silently or whether you speak aloud.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. The proper nouns, as well as the Greek and Hebrew:

1) The noun is Pelishetîy (פְּלִשְתִּי) [pronounced pe-lish-TEE], and it stands for Philistine. We obviously transliterate this Philistine. Strong’s #6430 BDB #814. The corresponding Greek noun in the Septuagint in this passage is the plural of ̓allophulos (ἀλλόφυλος) [pronounced al-LOW-fu-los], and this actually means foreign (from a Jewish standpoint), Gentile, heathen. Interestingly enough, we don’t have a transliteration here. Strong’s #246 Arndt & Gingrich #40.

2) The second related Hebrew noun is Phelesheth (פְּלֶשֶת) [pronounced pe-LEH-sheth], which is transliterated Palestine, Philistia, Philistines, Palestina. Strong’s #6429 BDB #814. Whereas the previous noun is found well over 200 times in Hebrew Scripture, this is found but eight times. I could not locate the corresponding Greek noun in any of my Greek dictionaries.

3) We find this name in the Egyptian records of Ramses III (circa 1188 b.c.) as prst (the Hieroglyphic

replaces the l with an r).

![]() We also find the Pilisti and Palastu in Assyrian texts of roughly the same time

period.

We also find the Pilisti and Palastu in Assyrian texts of roughly the same time

period.

4) The Israelites also referred to them as the uncircumcised, which was a term of derision. Apparently the Edomites, Ammonites, Moabites and Egyptians circumcised their children (Jer. 9:25–26).

2. The origins of the Philistines:

![]()

1) The first and clearest option is that the Philistines did originate from the very elusive Casluhim, whose name appears but twice in Scripture and whose background is not known at all. We know the genetic line of the Casluhim, both nothing more than that. The passages of Gen. 10:13–14 and I Chron. 1:11–12 state that the Philistines were ultimately born of the Egyptians (Mizraim). They quite possibly left Egypt by sea to become a people to themselves. This would mean that the Philistines would have lived in or taken over areas known to belong to the Caphtorim (for a sea people, this would not be unlikely). However, given their altercations with the Egyptians, we must assume if there is any common ancestry, that it goes very far back.

2) The Philistines lived in Caphtor long enough to be identified as coming from Caphtor (which is possibly Crete). Jer. 47:4 Amos 9:7 are both quoted to support this. Jer. 47:4 reads: “On account of the day that is coming—to destroy all the Philistines, to cut off from Tyre and Sidon , every ally that is left; for Jehovah is going to destroy the Philistines, the remnant of the coast land of Caphtor.” As you can read, although a case could be made for them coming from Caphtor from this verse, it is not conclusive. Amos 9:7 is more clear, however: “Did I not bring Israel out of the land of Egypt? And the Philistines from Caphtor? And Aram from Kir?” Now, this passage does not prove that Israelites are Egyptians; therefore, it does not prove that Philistines are descended from the people of Caphtor.

3) The next problem is, is Caphtor Crete? In Jer. 47:4, quoted above, there is a reference to the coast land

of Caphtor. This is the Hebrew word ʾîy (אִי) [pronounced ee], which means coast, region, border. There

is a form of this word which means island(s), but that is not found in Jer. 47:4. My thinking is that the

plural of this noun indicates several coasts, meaning that we are speaking of an island. Strong’s #339

BDB #15. The upshot of this point is that Jer. 47:4 does not tell us that Caphtor is an island. ZPEB gives

some evidence that Caphtor might be Crete by tracing out some Egyptian proper names which could

stand for Caphtor and for Crete. The points that they make are, however, inconclusive.

![]() Conder, in The

International Standard Bible Encyclopedia covers the same Egyptian words, and clearly points out that

we cannot draw the conclusion that Caphtor = Crete.

Conder, in The

International Standard Bible Encyclopedia covers the same Egyptian words, and clearly points out that

we cannot draw the conclusion that Caphtor = Crete.

![]()

4) In Ezek. 25:16, we read: Therefore, thus says Jehovah God, “Behold, I will stretch out My hand against

the Philistines, even and (or, even) off the Cherethites and destroy the remnant of the seacoast.” In the

Greek, Cherethites is translated Cretans. We have a similar passage in Zeph. 2:5. While both passages

clearly associate the Cherethites with the Philistines, neither passage unequivocally equates the two

peoples. Furthermore, although the Septuagint fairly clearly identifies the Cherethites with Crete, there

are even disagreements even here.

![]() Although I cannot be dogmatic at this point, it is less of a stretch

to identify the Cherethites with Crete than it is to identify Caphtor or the Philistines with the island Crete.

Although I cannot be dogmatic at this point, it is less of a stretch

to identify the Cherethites with Crete than it is to identify Caphtor or the Philistines with the island Crete.

5) To add to this confusion, because the Cherethites are associated with the Philistines in the previously mentioned passages; because the Cherethites are associated with the Pelethites in several other passages; and because the names Philistines and Pelethites are so similar in the Hebrew, these two peoples are thought to be equivalent.

6) Now, many Biblical scholars

![]() identify the Philistines with the Caphtorim; yet an unequivocal statement

of Scripture is lacking (although inferences could obviously be drawn from passages such as Amos 9:7).

Moses, prior to Israel going into the land, and clearly after the Philistines had established a firm hold on

the coast of Palestine, refers to the Caphtorim as having come from Caphtor and who occupied Gaza,

wresting it from the Avvim

identify the Philistines with the Caphtorim; yet an unequivocal statement

of Scripture is lacking (although inferences could obviously be drawn from passages such as Amos 9:7).

Moses, prior to Israel going into the land, and clearly after the Philistines had established a firm hold on

the coast of Palestine, refers to the Caphtorim as having come from Caphtor and who occupied Gaza,

wresting it from the Avvim

![]() (Deut. 2:23).

(Deut. 2:23).

7) What appears to be the most popular theory is that the Philistines are a non-Semitic people who originated from the Aegean area, and probably from the Island of Crete. We then would have a problem with Gen. 10:14, which reads: ...and Pathrusim and Casluhim (from whence [came] the Philistines) and Caphtorim. I Chron. 1:12 reads the same way. Whereas, we could write off Gen. 10:14 to anachronism (i.e., someone inserted the phrase later, and in the wrong place); it is more difficult to accept that something similar happened in the case of I Chron. 1:12 (and simultaneously accept the infallibility of Scripture). Even if I Chron. 1:12 was based upon the Genesis manuscripts of that day, then the guiding hand of the Holy Spirit would have struck that phrase or correctly placed it. There is the other possibility that this phrase was added by the same person to both portions of Scripture, which is definitely a possibility, but unlikely. The NRSV and the NEB both place the offending phrase with the Caphtorim, the NRSV noting that this is a correction which does not have any corroborative manuscript evidence. The REB also footnotes that and the Caphtorites is incorrectly placed, noting Amos 9:7. Just bear in mind that the moving of that portion of Scripture is based entirely upon presuppositions of the origins of the Philistines and not upon any manuscript evidence (and that two passages of Scripture are affected here, not just one).

8) In I Sam. 30:14, a portion of the Philistine coast is called Negev of the Cherethites, a name which probably refers to Cretans. In both Ezek. 25:16 and Zeph. 2:5–6, the Philistines and the Cherethites are mentioned together more in a parallelism, rather than as different groups of peoples. However, we have examined both passages, and we know that this cannot be stated unequivocally.

9) Egyptian records, unearthed by archeologists, reveal a sea people who:

(1) Came from islands in the north.

(2) Caused tremendous upheaval in the ancient near East circa 1200 b.c.

(3) Caused the downfall of the Hittites and their capital city, Hattusas.

(4) They attacked Egypt during the

reigns of Merneptah and

Ramses III.

![]()

(5) Obviously, these people could have been Philistines, Cherethites, Pelethites, and/or Cretans—therefore, this historical information does not allow us to identify the Philistines.

10) The pottery and artifacts which belonged to the Philistines appear to be have Mycenaean elements rather

than a Minoan origin. The Mycenaean pottery was known for its leather colored cups and jars, as well

as geometric patterns of black and red, and pictures of swans cleaning their feathers. In any case, at

the time of the arrival of the Philistines to the coastal areas of Palestine, we also find the introduction of

a new sort of pottery, very similar to the Mycenaean pottery, which is ascribed to the Philistines. The

pottery of the Mycenaeans was introduced around 1400 b.c. and was a very popular pottery. It was

found all over the ancient world as the result of trading and exporting. When Mycenae was destroyed

shortly before 1200 b.c., this export of pottery naturally ceased. It is guessed that these Philistines came

by way of Mycenae and ended up on the Palestine coast.

![]()

11) The Philistines apparently found how to smelt iron from the Hittites, whom they apparently conquered, and they fully exploited this patent. They guarded the secret of smelting iron, recognizing that they had a unique and powerful monopoly in the ancient world. We might guess that their defeat at the hands of Egypt, soon followed by these attacks by Samson, kept them from becoming the most powerful nation of the ancient world. With their monopoly of the smelting of iron, with their great ships, and with their aggressive, war-like behavior, it is surprising and almost a mystery why they were not the dominant power at that time in the ancient world. We know that it was simply not God’s plan for that to happen.

12) It is uncertain whether the Philistines traveled through and stayed at Crete for a short time or whether they actually originated at Crete.

13) One of the questions of the origin deals with their names—many of the names of the Philistine kings and

cities are Semitic in origin. In fact, all nine of the proper names as well as the geographical names

related to the Philistines appear to be of Semitic origin.

![]() In fact, because of these proper names, some

theologians identify the Philistines as a Semitic people. However, Scripture indicates that the Philistines

had lived in the Land of Promise since the days of the patriarchs, and actually being a small, but definite

power during their time. Therefore, the fact that many of their names sound Semitic would be expected

of a small, quiet settlement of peaceful peoples, who originally assimilated quietly into the Land of

Promise.

In fact, because of these proper names, some

theologians identify the Philistines as a Semitic people. However, Scripture indicates that the Philistines

had lived in the Land of Promise since the days of the patriarchs, and actually being a small, but definite

power during their time. Therefore, the fact that many of their names sound Semitic would be expected

of a small, quiet settlement of peaceful peoples, who originally assimilated quietly into the Land of

Promise.

14) Keller gives us the most colorful account of their

approach to the Land of Promise: Fragments of

pottery, inscriptions in temples and traces of

burnt-out cities gives us a mosaic depicting the

first appearance of these Philistines, which is

unrivalled in its dramatic effect. Terrifying

reports heralded the approach of these alien

people. Messengers brought evil tidings of

these unknown strangers who appeared on the

edge of the civilised ancient world, on the coast

of Greece. Ox-waggons, heavy carts with solid

wheels, drawn by hump-backed bullocks, piled

high with household utensils and furniture,

accompanied by women and children, made

their steady advance. In front marched armed

me. They carried round shields and bronze swords. A thick cloud of dust enveloped them, for there were

masses of them. Nobody knew where they came from. The enormous trek was first sighted at the Sea

of Marmora. From there it made its way southwards along the Mediterranean coast. On its green waters

sailed a proud fleet in the same direction, a host of ships with high prows and a cargo of armed men.

Wherever this terrifying procession halted it left behind a trail of burning houses, ruined cities and

devastated crops. No man could stop these foreigners; they smashed all resistance. In Asia Minor,

towns and settlements fell before them. The mighty fortress of Chattusas on the Halys was destroyed.

The magnificent stud horses of Cilicia were seized as plunder. The treasures of the silver mines of

Tarsus were looted. The carefully guarded secret of the manufacture of iron, the most valuable metal

of the times, was wrested from the foundries beside the ore deposits. Under the impact of these shocks

one of the three great powers of the second millennium b.c. collapsed. The Hittite Empire was

obliterated. A fleet of the foreign conquerors arrived off Cyprus and occupied the island. By land the trek

continued, pressed on into northern Syria, reached Carchemish on the Euphrates and moved on up the

valley of Orontes. Caught in a pincer movement from sea and land, the rich seaports of the Phœnicians

fell before them. First Ugarit, then Byblos, Tyre and Sidon. Flames leapt from the cities of the fertile

coastal plain of Palestine. The Israelites must have seen this wave of destruction, as they looked down

from their highland fields and pastures, although the Bible tells us nothing about that. For Israel was not

affect. What went up in flames down there in the plains were the strongholds of the hated Canaanites.

![]()

15) We also know that the Philistines were heavy drinkers. Many of the drinking mug fragments found which

are associated with the Philistines are fitted with a filter, which would be used to filter their beer. The

barley husks floated in their home-made ale, and these filters kept these husks from being swallowed

inadvertently.

![]() There are at least two allusions to festive drinking in Judges (Judges 14:10 16:25); and

the contrast of Samson being a nondrinker because of his Nazarite vows, becomes more profound when

we realize this (in the Biblical narrative, this contrast is almost lost).

There are at least two allusions to festive drinking in Judges (Judges 14:10 16:25); and

the contrast of Samson being a nondrinker because of his Nazarite vows, becomes more profound when

we realize this (in the Biblical narrative, this contrast is almost lost).

16) Now, you may be curious as to why we have spent this amount of space on the origin of the Philistines, only to conclude that we have very few conclusions. I mention this as there are theories of the origins of the Philistines which are given in brief footnotes in various Bibles as though they are facts. These facts often lead to misunderstandings and alleged contradictions. What you should realize is that, although your Bible may footnote some passage with great authority, the footnote is not always accurate nor is it a part of Scripture.

17) To sum up what we do know:

(1) The Philistines were originally descended from the Egyptians, but far removed. They are descended

through the elusive Casluhim (Gen. 10:13–14 I Chron. 1:12).

![]() Arabs and Jews are more closely

related.

Arabs and Jews are more closely

related.

(2) The Philistines are related to the Cherethites, but they are not necessarily the same people. It is possible that the two peoples merged in the land of Palestine.

(3) The Philistines originally lived in Caphtor or occupied Caphtor, although we do not know for a fact where Caphtor is.

(4) The Philistines may be identical to the Pelethites.

(5) They built a relatively advanced society in Crete, Asia Minor and in the Greek mainland.

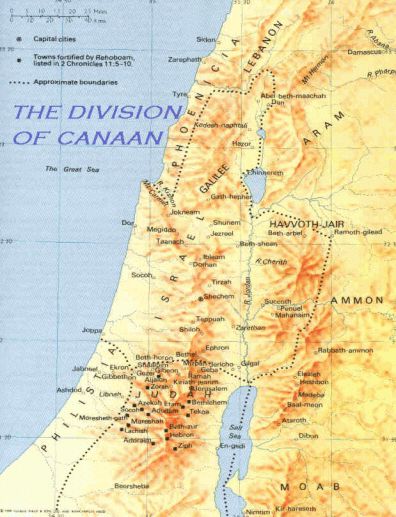

3. The Philistines occupied actually a fairly small area—they lived along the southern coast of Palestine between

Joppa and Gaza. The land was flat, the soil was fertile, this was an area of sea ports, and many trade routes

proceeded through this area; four things which made this land very desirable. They had originally set their

sights on Egypt, but were soundly defeated by Egypt at sea. Keller: In Medinet Habu west of Thebes on the

Nile stands the imposing ruin of the splendid temple of Amun, dating from the reign of Ramesses III

(1195–1164 b.c.). Its turreted gateway, its lofty columns, and the walls of its halls and courts are crammed

with carved reliefs and inscriptions. Thousands upon thousands of square feet filled with historical documents

carved in stone. The temple is one vast literary and pictorial record of the campaigns of the Pharaohs and

is the principal witness to events on the Nile at that time.

![]() Apparently, what happened in their battle at sea

is that the wind died down prior to the battle, which meant that the Philistines could not maneuver their

position. They were designed to do hand-to-hand combat with their swords and spears. The Egyptians

remained at a safe distance and rained their ship with arrows, killing a great many of the Philistines. The rest

were taken as POW’s. In fact, as far as I know, this might be the first recorded incident of POW camps.

Then prisoners themselves were branded with the name of Pharaoh on their skins. Now, whether these were

Philistines or a coalition of Philistines and other sea peoples, is not clear. In any case, the Philistines suffered

this tremendous defeat at the hands of Ramesses III in 1188 b.c. They then settled along the coast of

Palestine, to plague Israel instead.

Apparently, what happened in their battle at sea

is that the wind died down prior to the battle, which meant that the Philistines could not maneuver their

position. They were designed to do hand-to-hand combat with their swords and spears. The Egyptians

remained at a safe distance and rained their ship with arrows, killing a great many of the Philistines. The rest

were taken as POW’s. In fact, as far as I know, this might be the first recorded incident of POW camps.

Then prisoners themselves were branded with the name of Pharaoh on their skins. Now, whether these were

Philistines or a coalition of Philistines and other sea peoples, is not clear. In any case, the Philistines suffered

this tremendous defeat at the hands of Ramesses III in 1188 b.c. They then settled along the coast of

Palestine, to plague Israel instead.

![]()

4. There were five principal cities of Philistia (and I will take them from north to south):

1) Ekron was inland, in the land of Dan near the border of Judah and Dan, approximately 15–20 miles from the coast.

2) Ashdod was closer to the ocean and it had its own sea port. Sand dunes lay between Ashdod and the Mediterranean Sea.

3) Ashkelon, which was the only city located right on the coast of the Mediterranean.

4) Gath was inland almost directly 20 miles east from Ashkelon.

5) Gaza, which had its own sea port, also separated from the ocean by sand dunes.

5. Important cultural/government information about the Philistines:

1) The Philistines were ruled by five lords, one each for their principal cities (Joshua 13:3 I Sam. 6:4, 18). At some time during their history, there was one ruler over these five lords (I Sam. 29:1–7).

2) Throughout Scripture, there is never an indication of any sort of a language barrier between the

Philistines and the Hebrews. One view is that they adopted the language of the area that they moved

to; another is that they became multi-lingual, which is not unusual for European peoples. What we do

not have is any writings from the Philistines, although there are several suggested loan words (words

adopted by the Israelites which came from another language; in this case, from the Philistines).

![]()

3) We know little about their religion, and that only from Scripture. Their three gods, which are mentioned in the Bible, are Dagon, Ashtaroth and Beelzebub, which are Semitic names. There were temples to Dagon in Gaza (Judges 16:21, 23–30) and in Ashdod (I Sam. 5:1–7); temples to Ashtaroth in Ashkelon (Herodotus I. 105).

6. The history of the Philistines in Palestine and their relationship to Israel:

1) The first mentioned of the Philistines occurs way back in Gen. 20 21:22–34 26.

(1) You may recall the story of Gen. 20, when Abraham made the dumb decision to tell everyone that Sarah was his sister rather than his wife. Abimelech, the king of Philistia, took her as his wife. God spoke to Abimelech in a dream and put an end to that foolishness. Abimelech invited Abraham to stay in his country and to live wherever he wanted to.

(2) Abraham did have some problems with some individual Philistines, which Abimelech straightened out. Abraham made a covenant with Abimelech and his commander-in-chief, Phicol, in Beersheba, which is forty miles inland from the coast.

(3) In the latter chapter, Isaac lived in Gerar, Abimelech, the king of the Philistines.

(4) Some think that these passages are anachronistic, as they believe that the Philistines did not move into the area of Palestine until 1200 b.c. and this would have taken place roughly 800 years earlier.

i When an anachronism occurs, there are usually great similarities to the time period from which the character was taken. For instance, here the Philistines occupy area as far as Beersheba, which was not the case later. They are ruled by a king, rather than by five lords. Nothing is said of their principal five cities from the time of the judges. Furthermore, the relationship between Abimelech, their king, and the patriarchs, was amiable—quite the opposite of their dealings with Israel during the time of the judges. Anachronisms generally do not work this way. The territories and relationships are not changed when inserted into a passage.

ii There are a number of possible explanations: these peoples may have later merged with the sea peoples, and the name that was taken was from them. This may have been a very early settlement of the sea people, which later increased in size.

iii There is no extra-Biblical evidence at this time to support these passages; however, the accuracy of the history of the Bible has been vindicated over and over again by archeology.

iv You must understand when historical scholars question the existence of the Philistines in the

land, it is not based upon evidence which they have found, but based on the fact that they

haven’t found any corroborating evidence. We do not have, for instance, any writing which we

can attribute to the Philistines; this does not mean that they did not have a language or that they

did not have a written language. There is no specific evidence outside of the Bible which

indicates that the Philistines did not live in the land either. Every Biblical indication is that they

were a small, peaceful settlement during the time of the patriarchs, which is why they might

have made it under the radar of Egyptian documents. Furthermore, there were perhaps several

groups of sea peoples, who were not necessarily distinguished in extra-Biblical sources until the

Philistines became a military force.

![]()

2) During the time of the exodus, the Philistines definitely lived along the coastline of Palestine, as we note in Ex. 13:17, where God does not lead Israel along the coast into the Land of Promise, so that they are not dissuaded by entering directly into war with the Philistines (whose behavior had obviously changed dramatically over a few centuries). At that point in time, they had not only a firm grip upon the land where they dwelt, but upon the sea, as the Mediterranean Sea is called the sea of the Philistines in Ex. 23:31.

3) The relationship between Egypt and the Philistines is not clear at this time. There were Philistine colonies in the 12th and 11th centuries b.c. in Egypt (along the Nile Delta and in Nubia, which is in southern Egypt), yet Ramses III speaks of repulsing the Sea peoples circa 1188 b.c. During the time when Egypt dominated Canaan, the Philistines settled there. ZPEB suggests that these settlements may have been sanctioned by Egypt. Such a relationship would explain why the Philistines took great pains to preserve certain Egyptian artifacts placed in the temple at Beth-shan by an Egyptian garrison.

4) You may wonder why the Philistines moved into the Land of Promise in the first place. The first guess

is that it is on the Mediterranean Sea; however, the problem with that is that there are actually very few

natural sea ports along the coast of Israel, which is one reason why the men of Israel never became men

of the sea.

![]() Apparently, the limited access to the coast by other ships, and the beautiful and rich land

is what captured the attention of the Philistines. San Francisco similarly draws huge numbers of people

based upon its beauty alone (although it is a great sea port as well).

Apparently, the limited access to the coast by other ships, and the beautiful and rich land

is what captured the attention of the Philistines. San Francisco similarly draws huge numbers of people

based upon its beauty alone (although it is a great sea port as well).

5) There does not appear to have been a wholesale invasion of Canaan by these sea peoples, which resulted in the wiping out of the indigenous Canaanites. It appears as though the Philistines subjugated the Canaanite population, taking on many parts of the Canaanite culture at the same time. Apart from Ekron, it appears as though their cites all had substantial Canaanite populations. Again, if the Philistines began living in the land several centuries before as a peaceful people, this would make more sense that they were partially assimilated.

6) In the book of Joshua, we do not have any confrontations between Israel and the Philistines, although they are mentioned in Joshua 13:3 as occupying the five previously-mentioned cities.

(1) At first, the Philistines lived right along the shore in smaller numbers, with a couple of cities which were slightly inland.

(2) Israel occupied Judah, but primarily the hill country and the mountains.

(3) Therefore, between the inhabitants of Judah and Philistia was a large, mostly uninhabited valley. This large valley between them is why Israel and Philistia existed for a long time, side-by-side without any military clashes.

7) We are told that the Philistines, along with several other groups of peoples, were allowed to remain in the land to teach war to the Israelites (Judges 3:1–3).

8) Apparently, Israel did skirmish some with the Philistines, as Shamgar is said to have killed 600 of them with an ox-goad (Judges 3:31).

9) The Philistines are mentioned again in Judges 10:7, but that requires an explanation. The passage reads: And the anger of Jehovah burned against Israel, and He sold them into the hands of the Philistines, and into the hands of the sons of Ammon. Ammon was a problem to Israel from the east and the Philistines were problems west of Israel. What has occurred here is probably simultaneous, but independent attacks upon Israel. Israel and the Ammonites is discussed in Judges 11 and Israel vs. the Philistines is covered in Judges 13–16. The author of that portion of the book of Judges tells us in Judges 10:7 about what is to follow in the next several chapters (and implies that these are possibly simultaneous attacks).

10) It is possible that it was this Philistine domination which forced the tribe of Dan to seek another land to occupy in the far north (Judges 18). It is also possible that, due to impending conflict, that most of Dan already had migrated north, and that the Philistines enslaved those who remained.

11) We hear almost nothing about the Philistines until Judges 13–16, during the time of Samson, when the

Philistines subjugate the Israelites (more than likely, this would be Judah, Dan and Benjamin). What is

important in this passage is that Samson easily walked from his place in Zorah to interact with the

Philistines in Timnath, where he married a daughter of the Philistines (Judges 14:1). Zorah was also the

city where Delilah lived (Judges 16:4).

![]()

12) You may have some question as to the relative strengths and weaknesses of Israel and Philistia. After

all, Israel was a much larger population. However, Philistia was much better organized and their

weapons of war were much more advanced, being made of iron (I Sam. 13:19–22 II Sam. 1:6). From

Egyptian reliefs, the Philistines (prst) are shown, along with the Tjekker and Serdanu, as armed with

lances, round shields, long broadswords, and triangular daggers.

![]()

13) The Philistines would later attack Israel at Shiloh, destroy the holy city and then capture the ark there during the time of Eli (I Sam. 4). The reason for their victory, on the surface, would seem to be their greater organization and superior weapons, but there was a lot more to consider here (which will be covered in the exegesis of I Sam. 4).

14) Israel did enjoy a sensation victory over the Philistines sometime after that (I Sam. 7:7–14).

15) There was a continued Philistine presence in Geba (I Sam. 13:3), in Gibeah (I Sam. 14:1, 6, 15) and in Beth-shan (I Sam. 31:10–11) during the time of Samuel.

16) J. N. Birdsall suggests It was probably largely due to the continuing pressure of the Philistines that the

need for a strong military leader was felt in Israel.

![]()

17) Unfortunately, the Philistines still controlled vital portions of Israel (I Sam. 10:5 13:3–23 23). Birdsall suggests that they controlled Esdraelon, the coastal plain, the Negev and a significant portion of the hill country. The seemed to have a definite foothold in the middle of eastern Benjamin, which is quite a distance from the five cities. From here, they sent out raiding parties (I Sam. 13:17–23).

18) David developed a relationship with the Philistine king, Achish, while he was exiled from Israel. It

appeared for awhile that David would actually raise his sword against Israel during this alliance. In fact,

it is suggested, because of this relationship, that Achish was not really a Philistine, but a Canaanite king

who was a vassal of the Philistines.

![]()

19) The Philistines did defeat Saul and his sons in battle, yet allowed David to become king over Judah. David continued to struggle with the house of Saul over the throne (II Sam. 3:1). This is not inexplicable. On the one hand, the Philistines had a certain uneasy bond with David; and, on the other, it was easier to sit back and allow civil war to devastate Israel. Apparently the intention (and this is conjecture) of the more militant would be to go to war with whoever took over the throne, as many of the greatest soldiers of Israel would have died in the civil war. Philistia went to war against Israel as soon as David took the undisputed throne over Israel (II Sam. 5:17–25).

20) David took Gath and its territory (I Chron. 18:1) and probably Ekron, pushing the Philistines back to Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod. Interestingly enough, Gezer, which is west of Ekron, did not come under Israelite possession until Solomon’s rule (I Kings 9:16). ZPEB suggests that this was a political move on David’s part, as his army was no doubt strong enough to take it. Since the Pharaoh of Egypt had the authority to give Gezer to Israel (I Kings 9:16), this would imply that this was under Egyptian rule at that time, and that David left things that way (we could assume the same about Gaza, Ashkelon and Ashdod).

21) Part of David’s bodyguard were Cherethites, which he probably recruited out of the Philistines while he was in Ziklag (II Sam. 15:18). There is another theory given here by Conder, that these are not proper names, but titles; and we will take up that theory when we get to that passage. David was not just a popular king of Israel, he was a popular leader as well. Those of the Land of Promise who followed him did not do so as mercenaries, but as men who trusted David and his God.

7. It is at this point that we will temporarily end our Doctrine of the Philistines, and take the remainder of their history up at a later date. It is with the rule of David that the power and the influence of the Philistines dwindled and became inconsequential. ZPEB points out that the words Philistine and Philistines occur 149 times in the books of Samuel, but only six times in the books of Kings, indicating a rapid decline in their political and military influence. However, as a postscript to their power, Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, captured the remaining Philistine cities and deported the people and the rulers, which was the death of the Philistines as a separate and sovereign people.

8. And it is odd that this people, once a great thorn in the side of Israel for several centuries, is now barely a footnote in history.

1. Barnes’ Notes; Exodus to Ruth; F. C. Cook, editor; reprinted 1996 by Baker Books; p. . 2. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon; Hendrickson Publishers; Ⓟ1996; pp. . 3. The Englishman’s Hebrew Concordance of the Old Testament, George Wigram; Hendrickson Publishers, Ⓟ1997; First Printing, Appendix p. (46). 4. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia; James Orr, Editor; ©1956 Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Ⓟ by Hendrickson Publishers; Vol. ; p. . 5. Werner Keller, The Bible as History (second revised edition); New York, 1981; pp. 175–180. 6. New American Standard Bible, Study Edition; A. J. Holman Company, ©1975 by The Lockman Foundation. 7. The New Bible Dictionary; editor J. D. Douglas; ©Inter-Varsity Fellowship, 1962; Ⓟby W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; p. . 8. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible; James Strong, S.T.D., LL.D.; Abingdon Press, New York. 9. The World Book Encyclopedia; ©1983 by World Book, Inc.; Vol. B, p. , Vol. E, pp. . 10. The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible; Merrill Tenney, ed., Zondervan Publishing House, ©1976; Vol. 1, p. ; Vol. 5, p. . |

It is clear, when examining the sources of many the articles above that they have examined more ancient and better sources. However, there are so many hours in a day, so that, in order for me to do what I need to do, I need to stand upon the shoulders of hundreds of great Christian men who have preceded me. |